14 minutes

(Read 100) Deep Work

Release year: 2016

Author: Cal Newport

Review

This is a book about how to achieve focus when performing one’s task. Interestingly, it is not about efficiency. The hypothesis is that when we are deeply immersed in a task, efficiency will follow. In fact, pretty much everything one could hope for will follow from investing time working deeply, if we are to believe the author.

And you know what? I think he’s onto something! It’s clearly working for him, and looking back at my own experience, I can confirm that there is no worthy accomplishment that I achieved while multi-tasking.

The concept of deep work is central to the book, and here’s how Newport defines it:

Deep work: Professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skill and are hard to replicate.

This is in direct opposition to the concept of shallow work:

Shallow work: Noncognitively demanding logistical-style tasks, often performed while distracted.

Based on his personal experience, Newport proposes the “deep work hypothesis:”

Deep work hypothesis: The ability to perform deep work is becoming increasingly rare at exactly the same time it is becoming increasingly valuable in our economy. As a consequence, the few who cultivate this skill and make it the core of their working life will thrive.

Everything in the book hinges on this hypothesis. In fact, the first part of the book is entirely devoted to convincing us to adopt this hypothesis. Well, call me convinced! Personally, even before starting this read, I noticed that it has been becoming increasingly harder for me to be able to devote large chunks of my time for solving complex problems. The reasons are diverse: lack of interest, noisy environment, frequent context switching, the pull of social media, etc. At the same time, I have noticed that those around me that enjoyed promotions and peace of mind at work were those who were comfortable with sitting a long time deeply immersed with a problem and who didn’t feel intimidated by lack of immediate progress. Thus, the idea of deep work is compelling to me and I would like to learn how to turn it into a healthy habit in my life.

Thankfully, the second part of the book is dedicated to giving us every imaginable trick for reliably implementing deep work in our lives. I suppose the effect of those ideas will vary with each individual as a function of how willing we are to give them a try. Here are some of the ideas that stuck with me:

People are happier enjoying their job in a state of flow than enjoying unstructured free time.

This idea made me realize that there was indeed a period of my life where I naively assumed that having lots of free time would make me feel relaxed. Surprisingly, I often found the opposite happened, but it seems like I constantly make this mistake. For example, my partner would spend the day with some friends, leaving me free to do whatever I want at home. What often ended up happening is that I would just walk in circles in the living room trying to figure out the best way to spend my time. This was both incredibly stressful and wasteful. What I take away from this idea is that it’s ultimately better to look for an activity that I will be able to work long hours in, than to free my calendar and hope that having nothing to do will make me fulfilled.

Lagging vs leading measures

I really liked this reminder of leading vs lagging metrics. What defines a lagging measurement is that it is the result of a performance that is already in the past. For example, how fast a sprinter can run a hundred meters is a lagging metric, because it is a symptom of their physical fitness, their preparedness, etc. Another example of a lagging metric is a person’s body weight. It’s a function of what they ate and how much they moved.

Leading metrics are quantities we can directly control in the near future that we know will have a positive impact on our long-term goals. To use the same examples as above, we could say that how many hours per week our athlete spends training is a leading metric. For the foodie, how many grams of sugar they eat per meal would be a leading indicator. In both cases, this is something the person has direct control over.

The author recommends we keep track of how many hours we spend in deep work each day as a leading measure. That’s a much better indicator of future outcomes than tracking how many papers we published that year, or what’s our current salary, for example.

Shutdown rituals

At the end of a busy day, I often have trouble making sure that I have caught all loose ends and that there is no ball that I have dropped. The author suggests a ritual he does every day before leaving work, and this is a habit I’d really like to get good at. I suspect this will allow me to leave work less stressed and allow me to enjoy my life better.

- Ensure that every incomplete task, goal, or project has a plan you trust for its completion

- Ensure that every incomplete task, goal, or project is captured in a place where it will be revisited when the time is right.

- Take a final look at your inbox to ensure nothing requires an urgent response before the day ends.

- Transfer any new tasks into your official task list.

- With your task list(s) in view, skim every task on, and look at the next few days on your calendar. Use this information to make a plan for the next day.

- Say out loud a phrase that marks your shut down as complete.

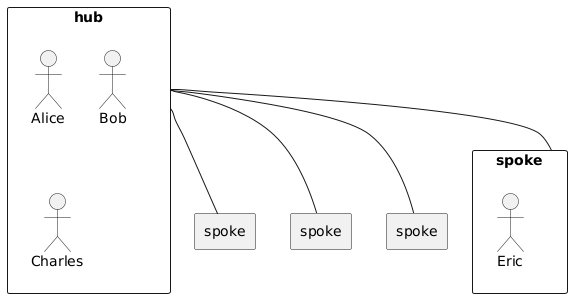

Hub and spoke architecture

This idea is mostly useful for people who have the power to shape the workplace in which they operate, but it is a powerful one to keep in mind nonetheless.

Basically, an optimal workplace configuration allows spaces that are designated for meeting people, making connections, and sharing ideas. These spaces allowing for serendipitous encounters are called hubs. Any open space office configuration contains a hub. Unfortunately, many open space offices lack an important component: spokes.

A spoke is an isolated space that allows someone to deeply focus, away from the noise and distraction of conversations taking place in the hub. The term “spoke” comes from the rod that connects the hub and the rim of a wheel. When someone is concentrated in a spoke, the agreement should be not to disturb them until they make themselves available in the hub.

This is a powerful way to work that, if well implemented in the workplace culture, will optimize how much deep work can be accomplished.

Quantifying depth

A simple idea, but a neat one in my opinion. For any task, there is a way to quantify it with a number. Sure, it will be an estimate, but it’s better than any qualitative estimate. The idea is to think how long it would take (in months) to train a smart recent college graduate with no specialized training in that field to complete this task.

For example, entering data in an Excel sheet? That’s not a deep task. Any recent college grad can easily learn how to do this within a month.

But designing a secure, scaling network architecture that allows for automated testing and alerts employees when downtime is detected? Yeah, that will take a while. Based on my own experience, I’d give this about 48 months easily.

This simple technique can be useful to help figure out in what mindset is required for the task at hand.

**Schedule distractions instead of deep work

The idea of scheduling distractions rather than deep work offers a counterintuitive yet effective strategy for maintaining focus. Instead of attempting to eliminate distractions entirely, which can often feel like an insurmountable challenge, this approach involves designating specific times for indulging in them. By creating “distraction windows,” such as a 15-minute break every two hours to check social media or respond to personal messages, individuals can enjoy these activities guilt-free without allowing them to seep into periods dedicated to meaningful, focused work. This structured approach reduces the allure of interruptions, as the promise of an upcoming break can make it easier to resist temptation in the moment. In doing so, scheduling distractions becomes a proactive method to balance leisure and productivity, reinforcing the boundaries necessary for deep work to flourish.

In conclusion

I appreciate that the author is very careful to nuance that not every hour of every day must be spent in deep work. In fact, he says we should strive for a budget of 30% to up to 50% of shallow work, which looks big to me! The reason he gives for this is that by taking deliberate breaks, we allow our unconscious to do its part in problem solving, which is to try to combine various elements present in our minds in order to generate new insights.

It’s very clear that the author attributes his success to his ability to consistently perform deep work. In this book, he is giving us his recipe to his success. No recipe can work for everyone, but I believe most of what Newport is saying falls under common sense and is worth giving a serious shot. For a start, just the nomenclature of deep / shallow work is useful to be more mindful about the quality of the work we are actually creating.

Félix rating:

👍

👍

Questions

What is the book about as a whole?

The book is about, unsurprisingly, deep work, which designates professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit.

What is being said in detail, and how?

The authors distinguishes “deep” work from “shallow” work, stating that deep work requires intense, distraction-free concentration that allows pushing one’s cognitive abilities to their limits. It is in this mental state that new skills are learned and value is created.

The book hinges on the hypothesis that in our modern society, deep work is becoming an increasingly rare commodity, which makes it an increasingly valuable skill to develop. The book argues that not only does deep work make us more productive, but it also leads us to live happier and more fulfilled lives. For this reason, the book’s main goal is to teach the reader how to incorporate deep work in their lives and goes on to provide many ideas for doing so.

Is the book true, in whole or part?

I believe the book is true in totality, as far as I can tell. Personally, my hobby of reading and reviewing books requires deep work, and this is something I constantly try to get better at. I can attest to the fact that every hour I have spent reading and reviewing books has been a worthwhile investment, certainly better than distracting myself consuming entertainment online like I used to for many years.

However, deep work is hard to constantly achieve, and it requires practice. I am not good at doing all kind of deep work, especially under stress. Thus, to me thus book represent a possible ideal that I can progress towards. I am certainly interested to try a few tricks from the author :

- measuring my “deep hours”

- performing shut down rituals

- scheduling distractions instead of deep work

What of it?

I think the book’s idea is a little self-evident (“The more focused you are when working, the better the results will be.”), but it is an idea that bears repeating. Many people today, myself included, believe that they can afford to multi-task without negatively impacting the tasks they are accomplishing. This is an enduring myth that we need to unlearn, and Deep Work provides compelling arguments towards busting that myth.

⭐ Star Quotes

Introduction

- (p. 11) To remain valuable in our economy, you must master the art of quickly learning complicated things. This task requires deep work.

Part I: The Idea

Chapter 1: Deep Work Is Valuable

- (p. 31) ⭐ If you can’t learn, you can’t thrive.

- (p. 32) If you don’t produce, you won’t thrive – no matter how skilled or talented you are.

- (p. 40) High-quality work produced = (Time spent) x (Intensity of focus)

- (p. 42) When you switch from some Task A to another Task B, a residue of your attention remains stuck thinking about the original task.

Chapter 2: Deep Work Is Rare

- (p. 62) Clarity about what matters provides clarity about what does not.

- (p. 64) In the absence of clear indicators of what it means to be productive and valuable in their jobs, many knowledge workers turn back toward an industrial indicator of productivity: doing lots of stuff in a visible manner.

Chapter 3: Deep Work Is Meaningful

- (p. 77) Our brains construct our worldview based on what we pay attention to. Who you are, what you think, feel, and do, what you love – is the sum of what you focus on.

- (p. 78) After a bad or disrupting occurrence in your life, what you choose to focus on exerts significant leverage on your attitude going forward.

- (p. 82) The idle mind is the devil’s workshop. When you lose focus, your mind tends to fix on what could be wrong with your life instead of what’s right.

- (p. 88) The task of a craftsman is not to generate meaning, but rather to cultivate in himself the skill of discerning the meanings that are already there.

Part II: The Rules

Rule #1: Work Deeply

- (p. 118) ⭐ Waiting for inspiration to strike is a terrible, terrible plan. Ignore inspiration. Great creative minds think like artists but work like accountants.

- (p. 133) The whiteboard effect: A shared whiteboard can push you deeper than if you were working alone. The presence of the other party waiting for your next insight can short circuit the natural instinct to avoid depth.

- (p. 135) It’s often straightforward to identify a strategy needed to achieve a goal (“what”), but what trips up companies is figuring out how to execute the strategy once identified.

- (p. 144) At the end of the workday, shut down your consideration of work issues until the next morning. Shut down work thinking completely. If you need more time, then extend your workday, but once you shut down, your mind must be left free.

- (p. 146) Providing your conscious brain time to rest enables your unconscious mind to take a shift sorting through your most complex professional challenges.

- (p. 149) The work that evening downtime replaces is usually not that important.

- (p. 151) Commit that once your workday shuts down, you cannot allow even the smallest incursion of professional concerns into your field of attention (including email and browsing work websites).

- (p. 153) Committing to a specific plan for a goal may not only facilitate attainment of the goal but may also free cognitive resources for other pursuits.

- (p. 154) When you work, work hard. When you’re done, be done.

Rule #2: Embrace Boredom

- (p. 161) ⭐ Instead of scheduling the occasional break from distraction do you can focus, you should instead schedule the occasional break from focus to give in to distraction.

- (p. 161) ⭐ Keep a notepad near your computer at work. On this pad, record the next time you’re allowed to be distracted.

- (p. 176) We’re not wired to quickly internalize abstract information. We are, however, really good at remembering scenes.

Rule #3: Quit Social Media

- (p. 191) Identify the core factors that determine success and happiness in your professional and personal life. Adopt a tool only if its positive impacts on these factors substantially outweigh its negative impacts.

- (p. 209) ⭐ Don’t use the Internet to entertain yourself.

- (p. 214) The mental faculties are capable of a continuous hard activity; they do not tire like an arm or a leg. All they want is change – not rest, except in sleep.

Rule #4: Drain the Shallows

- (p. 216) When you have fewer hours you usually spend them more wisely.

- (p. 222) ⭐ Adopt the habit of pausing before action and asking, “What makes the most sense right now?”

- (p. 226) ⭐ Continually take a moment throughout your day and ask: “What makes sense for me to do with the time that remains?”

- (p. 235) ⭐ A job that doesn’t support deep work is not a job that can help you succeed in our current information economy.

- (p. 236) Finish your work by five thirty.

- (p. 239) Be incredibly cautious about your use of the most dangerous word in one’s productivity vocabulary: “yes.”

- (p. 239) ⭐ Be clear in your refusal, but ambiguous in your explanation for the refusal. Avoid providing enough specificity about the excuse that the requester has the opportunity to defuse it.

- (p. 240) ⭐ In turning down obligations, resist the urge to offer a consolation prize that ends up devouring almost as much of your schedule.

- (p. 241) ✅ The fact that your boss happens to be clearing their inbox at night doesn’t mean that they expect an immediate response.

- (p. 255) Tim Ferriss: “Develop the habit of letting small bad things happen. If you don’t you’ll never find the time for the life-changing big things.”