10 minutes

(Read 22) Shape Up

Release year: 2019

Author: Ryan Singer

Buy the book (free online version )

Review

Really clever framework that has the potential to replace Agile and Scrum. It turns development into a game. I hope I’ll get to try it out someday. Everything just clicks! This book is also available online for free (Thanks Benoît Dicaire for this recommendation!)

Félix rating:

👍👍

👍👍

⭐ Star quotes

- (p. 14)The idea of Shape Up is to focus less on estimates and more on our

appetite.

- ❌ “How much time will it take?”

- ✅ “How much time do we want to spend?”

- ✅ “How much is this idea worth?”

- (p. 15) Shaping: Narrowing down the problem and designing the outline of a solution that fits within the constraints of our appetite

- (p. 25) Shaped work indicates what not to do, where to stop. It calls out any specific cases not supported. It creates boundaries that act like guard rails.

- (p. 26) To be a shaper, you don’t need to be a programmer, but you need to

be technically literate. You should be able to judge:

- what’s possible

- what’s easy

- what’s hard

- (p. 26) Shaping is a closed-door, creative process, a kind of private, rough early work. The work on the shaping track is kept private and not shared with the wider team until the commitment has been made to bet on it.

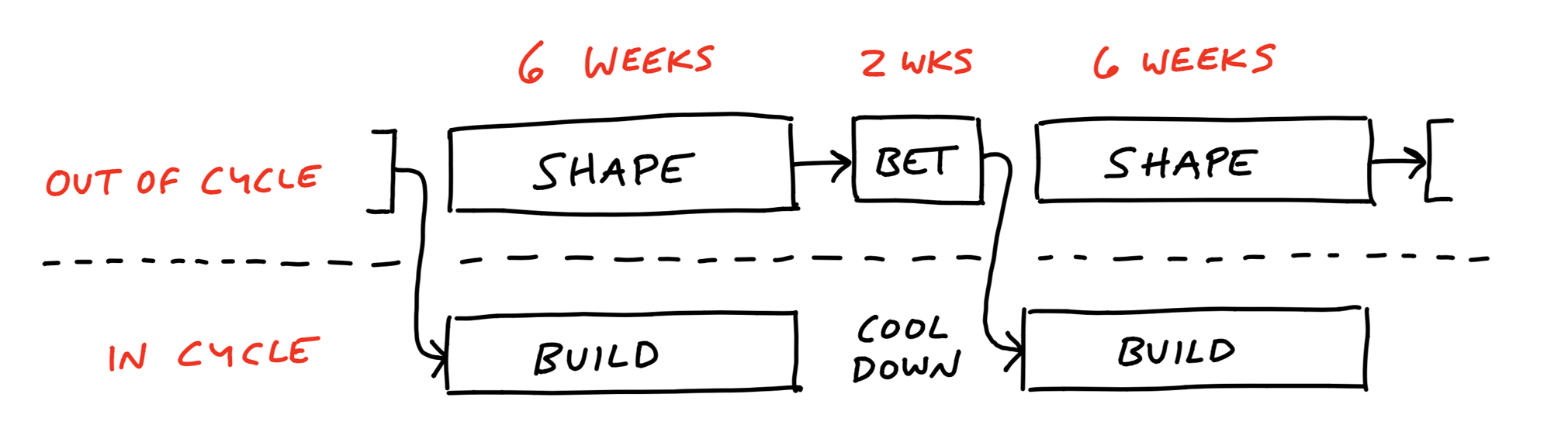

- (p. 26) During the six weeks cycle, teams are building work that’s been previously shaped, while shapers are working on what the teams might potentially build in a future cycle.

- (p. 27) Steps to shaping:

- Set boundaries (what is our appetite?).

- Create an idea that solves the problem within the appetite, but without all the fine details worked out.

- Address risks and rabbit holes.

- Write the pitch that will be reviewed at the betting table.

- (p. 29)

- Estimates start be a design and end with a number.

- Appetites start with a number and end with a design. The appetite acts as a creative constraint on the design process.

- (p. 30) There is no absolute definition of “the best” solution. The best is relative to your constraints.

- (p. 32) Finding the real problem to solve: At what point specifically does someone’s current workflow

break down without this thing they’re asking for?

- “Instead of asking her why she wants a calendar and what it should look like, we asked her when she wanted a calendar. What was she doing when the thought occurred to ask for it?”

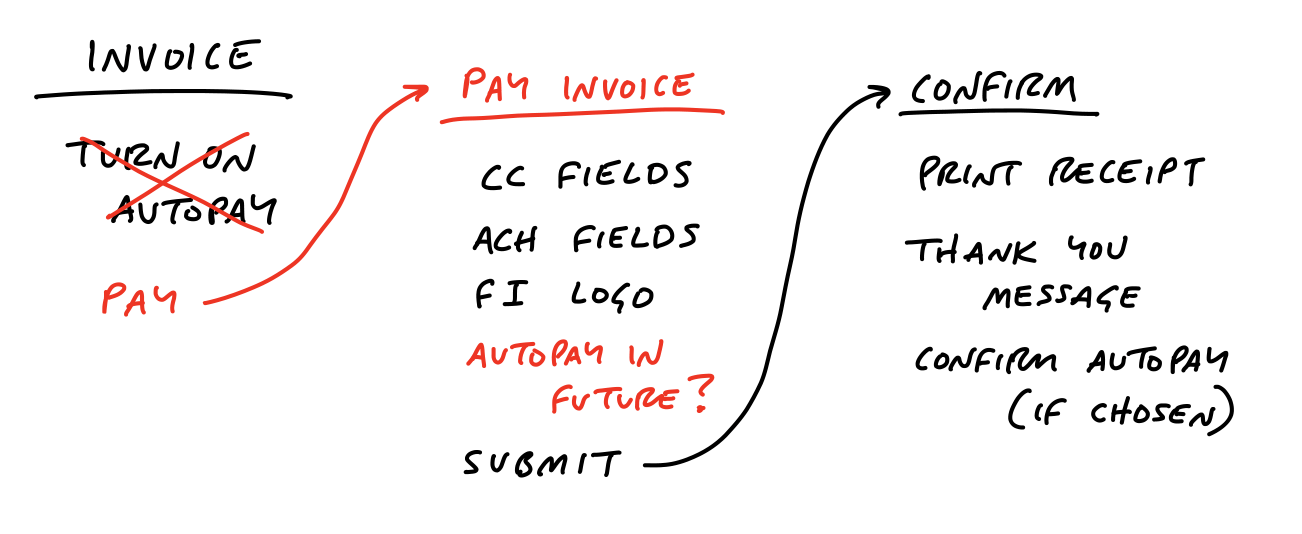

- (p. 37) When breadboarding, what matters are the components and

their connections (not pictures) to judge if the sequence of actions solves the use

case:

-

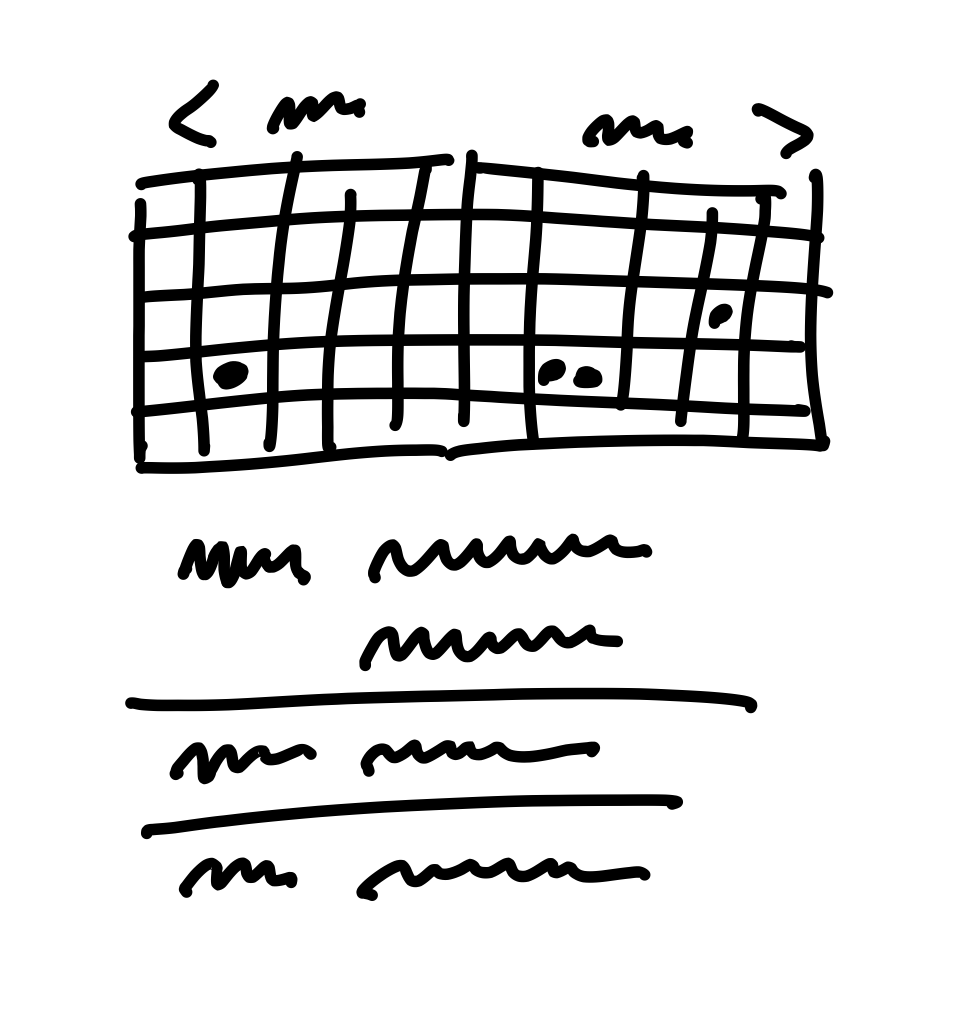

- (p. 41) Use fat marker sketches when the 2D arrangement of elements

is the fundamental problem. Make such broad strokes that adding detail

is difficult/impossible.

- Large Sharpies on a sheet of paper

- iPad drawing with the largest diameter pen size

-

- (p. 46) The output of breadboarding and fat marker sketches are not specs. They are the boundaries and rules of a game.

- (p. 47) At the shaping stage, we could walk away from the project. We haven’t bet on it.

- (p. 55) ⭐ When discussing with technical experts, instead of asking, “Is it possible to do X?” ask “Is X possible in 6 weeks?” and emphasize you’re looking for risks that could blow up the project.

- (p. 55) Rather than writing up a document or creating a slideshow, invite experts to a whiteboard and redraw the elements s you worked them out earlier, building up the concept from the beginning.

- (p. 58-60, 64) Five ingredients to always include in a pitch:

- The problem: Why the status quo doesn’t work.

- This gives you something to test against.

- An appetite: How much time we want to spend and how much that

constrains the solution.

- There’s always a better solution.

- A solution: The core elements we came up with presented in a

form that’s easy to immediately understand.

- Fat marker sketches can be very effective if labeled cleanly.

- Rabbit holes

- No-gos: Anything specifically excluded from the concept to fit the appetite.

- The problem: Why the status quo doesn’t work.

- (p. 67) For presenting a pitch, use asynchronous communication by default and escalate to real-time only when necessary. Pitches could be tracked as Jira tickets or messages on Slack.

- (p. People comment on the pitches asynchronously. Not to say yes or no (that happens at the betting table) but to poke holes or contribute missing information.

- (p. 72) Pitches don’t go in a backlog! Before each six weeks cycle, the betting table looks at pitches from the last six weeks, including pitches that somebody purposefully revived and lobbied for again. This removes grooming.

- (p. 73) If we don’t bet on a pitch, we let it go. There’s nothing we need to track or hold on to.

- (p. 76) After each six week cycle, we schedule two weeks for

cool-down. This is a period with no scheduled work where we can

breathe, meet as needed, and consider what to do next.

- Programmers and designers use this time to fix bugs, explore new ideas, try out new technical possibilities.

- (p. 77) The betting table is a meeting held during cool-down where stakeholders decide what to do in the next cycle.

- (p. 77) At Basecamp, the betting table consists of:

- CEO (they are the last word on the product)

- CTO

- A senior programmer

- A product strategist

- Buy-in from the very top makes cycles turn properly.

- (p. 78) The betting table rarely lasts longer than an hour or two. It requires everyone to have had a chance to study the pitches on their own time beforehand.

- (p. 78) The betting table gives the C-suite a “hands on the wheel” feeling.

- (p. 78) We talk about “betting” instead of planning because it sets different expectations.

- (p. 79) When you make a bet, you honor it. Don’t allow the team to be interrupted or pulled away to do other things.

- (p. 82) The vast majority of bugs can wait six weeks or longer and many don’t even need to be fixed.

- (p. 82) If a bug is too big to fix during a cool-down, it can compete for resources at the betting table.

- (p. 82) Schedule a bug smash once a year, usually around

holidays, where a whole cycle is dedicated to fixing bugs.

- The holidays are a good time because it’s hard to get a normal project done when people aren’t around.

- (p. 90) Questions to ask at the betting table:

- Does the problem matter?

- Is the appetite right?

- Is the solution attractive?

- The betting table shouldn’t be used for doing the design

- Is this the right time?

- Are the right people available?

- (p. 93) After the bets are made, someone from the betting table will write a message that tells everyone which projects we’re betting on for the next cycle and who will be working on them.

- (p. 96) There is no designated “task master” or “architect” who splits the project into pieces. Trust the team to take on the entire project and work within the boundaries of the pitch.

- (p. 98) All testing and QA needs to happen within the cycle.

- (p. 98) We don’t expect these things to happen within the cycle, we

can do them during a cool-down:

- help documentation

- marketing updates

- announcements to customers

- (p. 99) When the cycle begins, arrange a kick-off call to walk through the shaped work. This gives the team a chance to ask any important questions that aren’t clear from the write-up.

- (p. 100) In the first few days of the cycle, expect radio silence. Everyone is busy learning the existing system and getting oriented. Only if the radio silence doesn’t start to break after three days, then step in to see what’s going on.

- (p. 101)

- Imagined tasks are tasks we think we need to do at the start of a project

- Discovered tasks are tasks we discover we need to do in the course of doing real work. These make the true bulk of the project and sometimes present the hardest challenges.

- (p. 102) The way to really figure out what needs to be done is to start doing real work.

- (p. 103) Teams should aim to make something tangible and demoable early (in the first week or so)

- (p. 110) First make it work, then make it beautiful.

- (p. 111) When you are early in the cycle, don’t slow down to implement something that won’t teach you anything about the problem you’re trying to solve (e.g. colors, handling data securely, etc.)

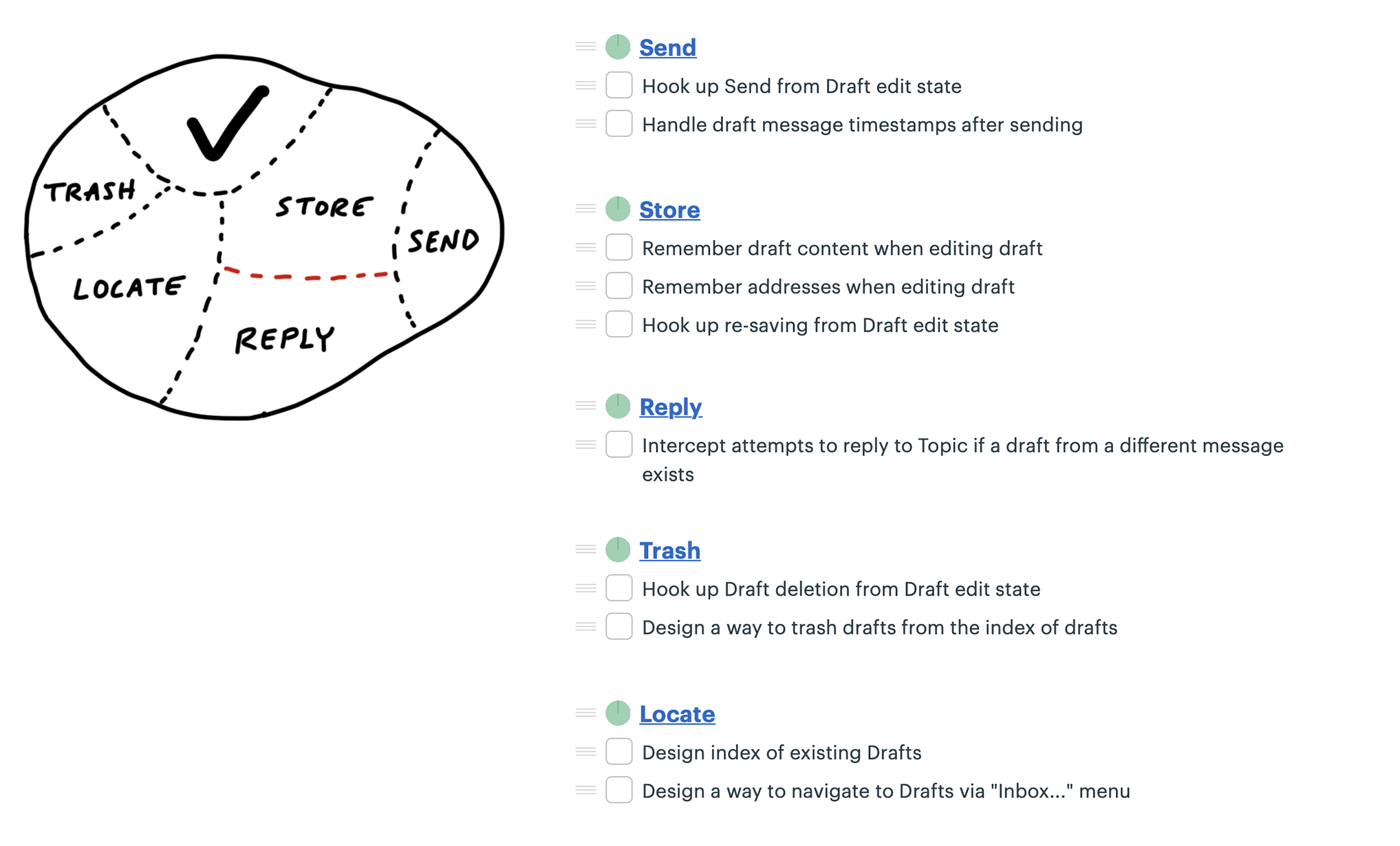

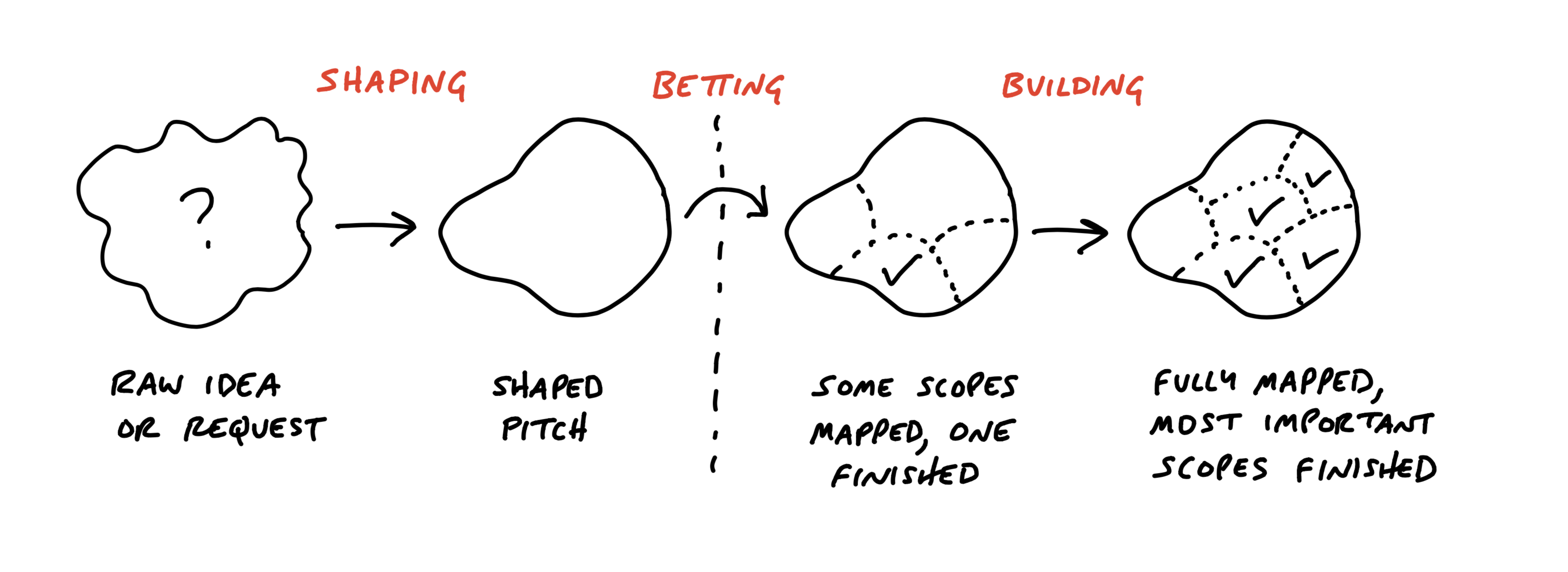

- (p. 116) The scopes reflect the meaningful parts of the problem

that can be completed independently and in a short period of time (few

days or less). In practice, we define and track scopes as to-do lists.

- More tasks will be discovered as work continues.

- (p. 122) Scoping isn’t planning. You need to walk the territory before you can draw the map, like in Starcraft.

- (p. 123) The scopes act like buckets that you can easily lob new tasks into.

- (p. 123) Three signs that indicate the scopes should be

redrawn:

- It’s hard to say how “done” a scope is. This happens when the tasks inside the scope are unrelated.

- The scope name isn’t unique to the project, like “front-end” or “bugs”. These are grab bags, or junk drawers.

- It’s too big to finish soon. Better break it up into pieces that can be solved in less time, so there are victories along the way and boundaries between the problems to solve.

- (p. 125) Icebergs are when there is significantly more backend

work than frontend work, or vice versa. For icebergs, it can help to

factor out the UI as a separate scope of work.

- Always question icebergs before accepting them as a fact.

- (p. 126) Do scope hammering by prefixing your nice-to-haves with “~” in the task list.

- (p. 127) Managers can’t rely on the to-do list status because it will grow as the team makes progress.

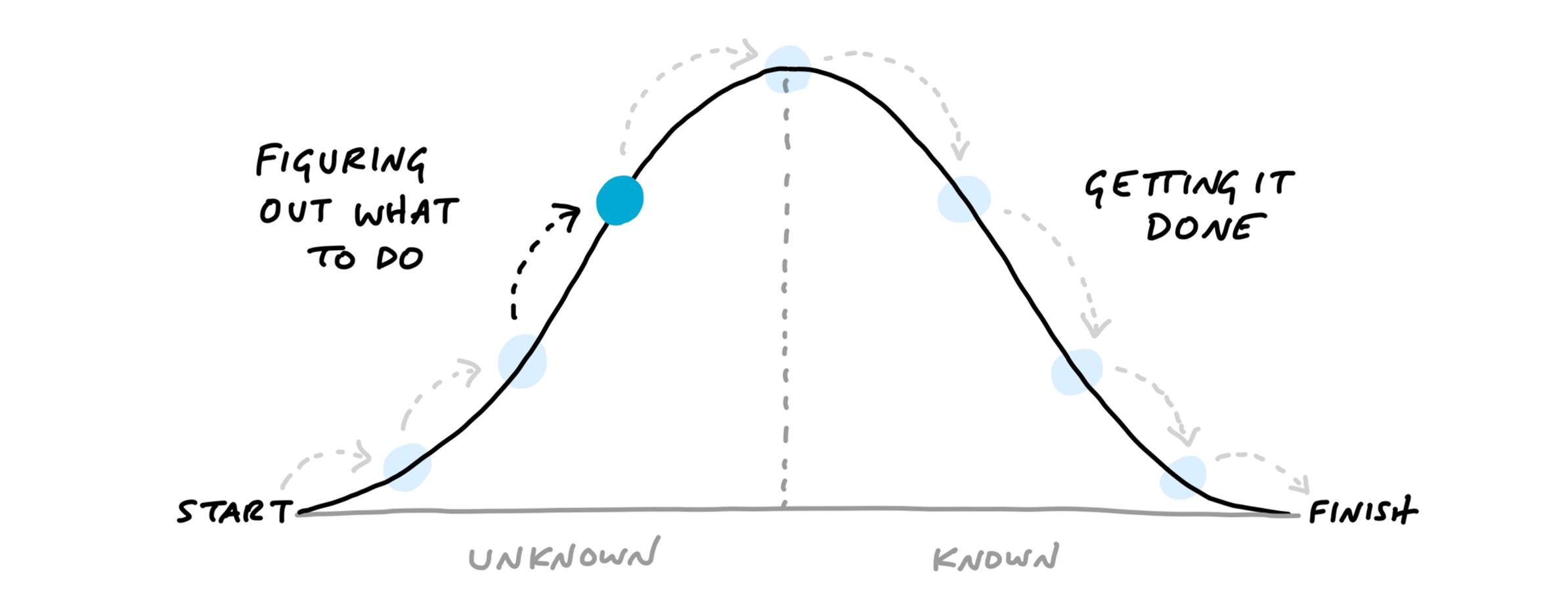

- (p. 133) The hill chart shows how the work on each scope feels at different

stages for each scope. For managers, it shows how the work is

moving. It removes the need to interrupt the team with status update

questions.

- (p. 136) When a point on a hill chart doesn’t move, it is effectively a raised hand: “Something might be wrong here. What can we solve to get over that hill?”

- (p. 139) Backsliding on the hill chart often means somebody did the uphill work with their head instead of their hands.

- (p. 142) Shipping on time means shipping something imperfect.

- “Okay, this isn’t perfect, but it definitely works and customers will feel like this is a big improvement for them.”

- (p. 145) Cutting scope isn’t lowering quality. Making choices makes the product better. It differentiates the product.

- (p. 146) Nice-to-haves ("~") can linger on a scope after it’s considered done. The scope isn’t considered done until must-have tasks are finished.

- (p. 148) QA generates “discovered tasks” that are all nice-to-haves ("~") by default.

- (p. 148) When to extend a project instead of letting the

circuit breaker do its thing:

- The outstanding tasks are true must-haves

- The outstanding work must be downhill

- Any uphill work at the end of the cycle shows an oversight in the shaping, or a hole in the concept.

- (p. 151) The raw ideas that just came in from customer feedback aren’t actionable yet. They too need to be shaped.

- (p. 169) How to begin doing Shape Up: A six-week experiment:

- Shape one significant project that can be comfortably finished within 6 weeks. Be conservative on your first run.

- Carve out one designer and two programmers’ time for the entire 6 weeks. Guarantee that nobody will interrupt them for the length of the experiment.

- Replace the real betting table with just the plan for the team to do the work you shaped for the experiment.

- Kick off by presenting your shaped work to the team, with all the ingredients of a pitch. Set the expectation that they will discover and track their own tasks.

- Dedicate a physical space or chat room to the cross-functional team so they can work closely together.

- Encourage them to Get One Piece Done by wiring UI and code together early in the project.

- (p. ?)

- (p. 168)

- Glossary

comments powered by Disqus